Archive

- Behind the Screens 9

- Bright Young Things 16

- Colour Palette 64

- Dress Ups 60

- Fashionisms 25

- Fashionistamatics 107

- Foreign Exchange 13

- From the Pages of… 81

- G.U.I.L.T. 10

- Little Trifles 126

- Lost and Found 89

- Odd Socks 130

- Out of the Album 39

- Red Carpet 3

- Silver Screen Style 33

- Sit Like a Lady! 29

- Spin, Flip, Click 34

- Vintage Rescue 20

- Vintage Style 157

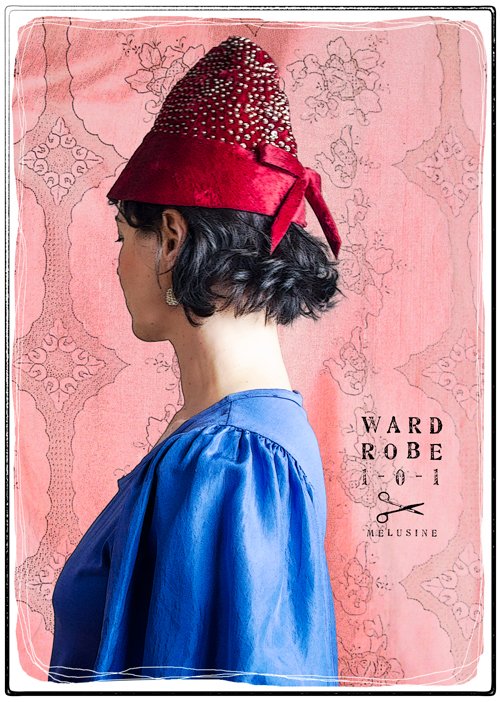

- Wardrobe 101 148

- What I Actually Wore 163

What is — and what is not — a fedora

THE DEFINITIVE GUIDE TO WHAT HAT IS THAT

If you have been reading this blog for a little while, you will know that I love hats. While I am not a trained milliner, I do own a lot of hats (over 300) and books about hats, which I sometimes even read (as opposed to drooling over the pictures). I scour the internet for strange and wonderful hats, and for a long time I have been looking for the perfect 1930s or 1940s fedora. I already own one (pictured above), which I love for its film noir aspect, but I would love one more that has a more exaggerated shape, specifically in a colour I love (not black or brown, which are more ubiquitous).

If you have been reading this blog for a little while, you will know that I love hats. While I am not a trained milliner, I do own a lot of hats (over 300) and books about hats, which I sometimes even read (as opposed to drooling over the pictures). I scour the internet for strange and wonderful hats, and for a long time I have been looking for the perfect 1930s or 1940s fedora. I already own one (pictured above), which I love for its film noir aspect, but I would love one more that has a more exaggerated shape, specifically in a colour I love (not black or brown, which are more ubiquitous).

What I am finding however, is that vintage sellers seem to apply the word ‘fedora’ to any vaguely mannish hat, and I’m not sure if that’s because some of them aren’t really clear on the proper definition of a fedora, or because it is an extremely popular search term – I’ve seen it applied as a keyword for a frothy pink, flower-bedecked garden party hat! Today, however, I am going to clear up any misconceptions about what is – and what is not – a fedora, with a few key, easy-to-remember points to identify these same, same but different hats.

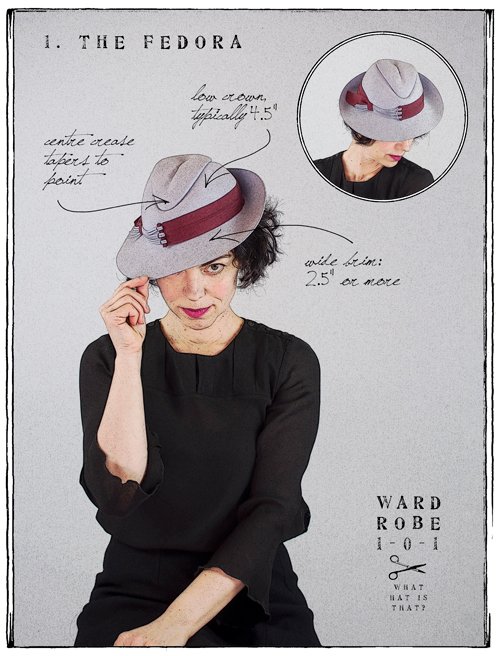

The Fedora

The Fedora

The fedora takes its name from an 1891 stage play, about a cross-dressing Princess Fedora who wears a centre-creased, soft wide-brimmed hat. Traditionally the crease is pinched at the front, forming a point or teardrop shape, but the crease can include diamond shaped crowns, and the positioning of dents can vary. Many other hats have centre dents, but the fedora combines this with a low crown – 4.5” or 11cm – and a wider brim of at least 2.5” or 6.4cm but they can be much wider, particularly in exaggerated fashion versions. The brims can be left raw, or stitched, or finished with ribbon-trim. This is the hat worn by Humphrey Bogart in the film Casablanca.

Key Points

- Low crown

- Centre crease pinched at front

- Wide brim

Humphrey Bogart in Casablanca; image found on Pinterest

Humphrey Bogart in Casablanca; image found on Pinterest

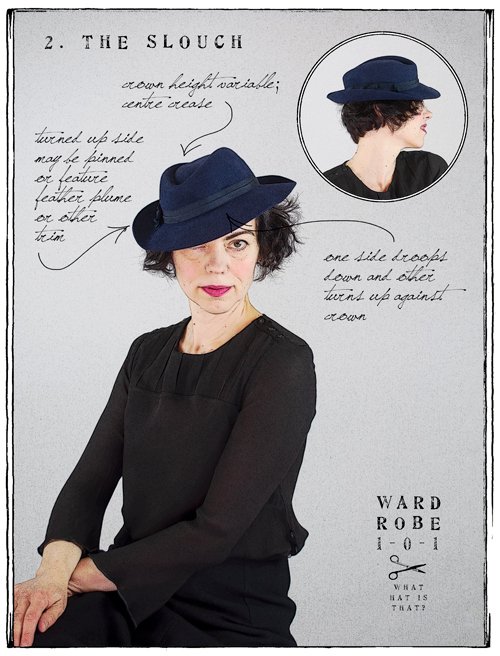

The Slouch

The next hat most commonly confused with a fedora, as far as I can discern, is the slouch hat. This is a style of hat traditionally worn by Australian soldiers (and those of many other nations), and is distinguished mainly with one side of the brim being turned up towards the crown, and one dipped down. The military hat has a fairly low crown, and the turned-up side is usually pinned to allow a rifle to be slung over the shoulder. Fashion versions vary in crown heights, but both feature a centre crease. Where the military hat is pinned up, the fashion hat may simply be decorated with trim on one side.

Key Points

- One side turned up, one side dipped down

- Crown height and brim width variable

- In place of the military pin, fashionable trim

Australian soldier wearing a slouch in 1916; image found on Pinterest

Australian soldier wearing a slouch in 1916; image found on Pinterest

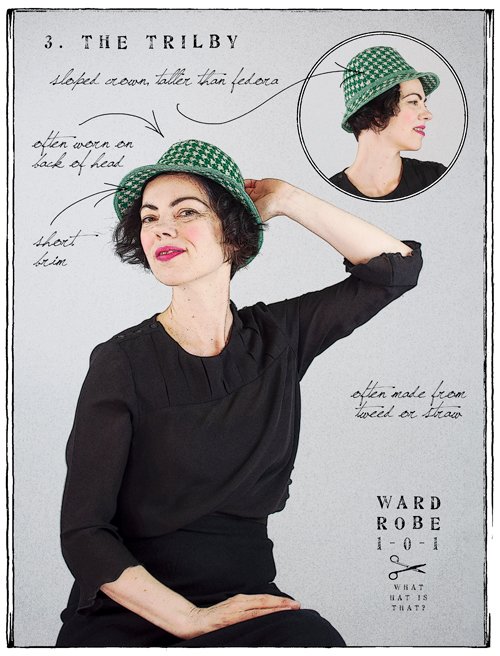

The Trilby

The Trilby

Another ubiquitous hat which can also be confused for a fedora is the trilby. Surprisingly, this is another hat whose inception lies in a stage play around the same time! George du Maurier’s 1894 novel Trilby was translated to the stage in London, and a hat of this shape was worn. Though the hat was worn by a woman, it became popular for men shortly after. It’s often made of tweed, like mine, or in straw for summer, though more properly its short brim is snapped up at the back. It has a much taller crown than a fedora, with sloped sides, and a popular hat with musicians, it is often worn on the back of the head. Sean Connery is well-known for wearing a trilby.

Key Points

- Short brim, usually snapped up at back

- Taller crown with sloping sides

- Designed to be worn further back on the head

Sean Connery wearing a trilby; image found on Pinterest

Sean Connery wearing a trilby; image found on Pinterest

The Homburg

The Homburg

The homburg is quite a masculine hat that has not really been translated into women’s versions, but this turquoise felt hat I own does not really fall into any other style, so I am using it to illustrate this style, perhaps most famously worn by Winston Churchill. Its most distinctive feature is the pencil-curled brim (which mine does not have at all). The hat is usually made of hard felt, with straight sides and a pronounced and quite wide centre crease. It is still a very popular hat shape for men today – and gangsters of all eras! Michael Corleone of The Godfather, and Nucky Thompson of Boardwalk Empire both present fine examples of the homburg’s sinister aspect.

Key Points

- Short, curled brim

- Taller crown with straight sides

- Wide, shallow centre crease

Winston Churchill was famous for his homburg; image found on Pinterest

Winston Churchill was famous for his homburg; image found on Pinterest

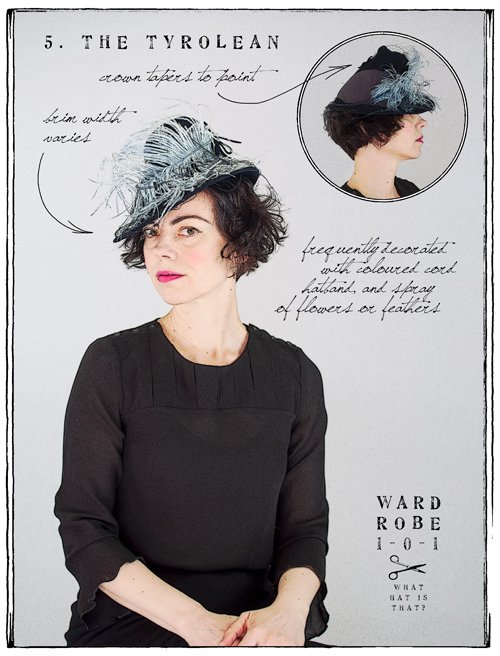

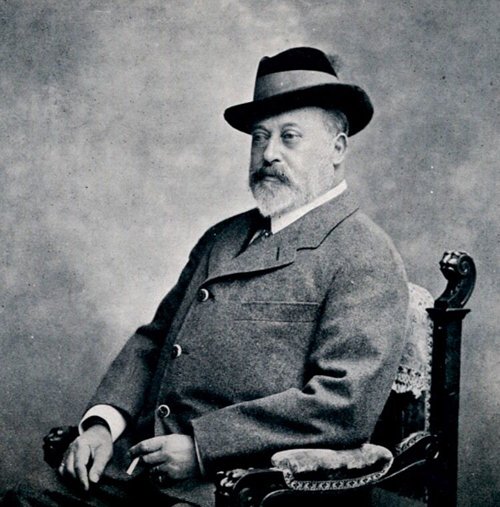

The Tyrolean

The Tyrolean hat style is one of my favourite jaunty styles! It originates from the Tyrol in the Alps, in what is now variously Austria, Germany, Italy and Switzerland. Its most distinctive feature is the crown that rises to form a point. The brim traditionally was roughly the width of a hand, and the hat was usually decorated with hatband made of coloured cord and a spray of flowers, feathers or brush. However, brims and crown heights varied in different parts of the Tyrol. Also known as a Bavarian or Alpine hat, it was originally made from green felt. Fortunately, fashion versions are not so limited in scope. Mine is navy, trimmed in a wide grosgrain band, netting, and a light blue ostrich feather. Edward VIII stayed in Austria after his abdication and often wore the hat, popularising its style.

Key Points

- Crown tapers to a point

- Crown height and brim width varies

- Decorated with flowers or feathers

Edward VIII made the Tyrolean hat famous after his abdication

Edward VIII made the Tyrolean hat famous after his abdication

In Conclusion

Of course, it must be remembered that these key points are only guidelines for identifying a general style – they are not hard and fast rules. Fashion hats often take inspiration from traditional styles and designers will add their own twist, pushing and pulling them in exaggerated directions, creating hybrids with brilliant details and wonderful new ideas. A hat should be the exclamation point of an outfit, the finishing touch to delight the eye – much more than a conservative tradition. But it’s always good to know the rules before you break them.

Photos: September 2019

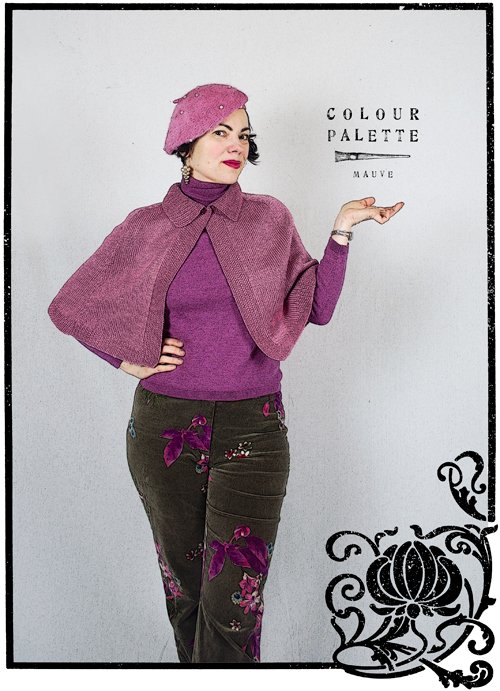

Marvellous Mauve

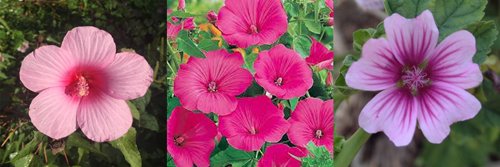

A couple of years ago I wrote a story about different shades of purple, and I touched on the discovery of the first aniline dye in 1856 that became known as mauve, the French word for mallow flower after which the colour is named. Originally it was probably a darker shade than contemporary notions of it, as it was first likened to Tyrian purple which is much darker. The first mauve dye was replaced with other synthetic dyes in 1873: a lighter, less-saturated shade that we are familiar with today. As Wikipedia succinctly describes it, ‘mauve contains more grey and more blue than a pale tint of magenta’.

A couple of years ago I wrote a story about different shades of purple, and I touched on the discovery of the first aniline dye in 1856 that became known as mauve, the French word for mallow flower after which the colour is named. Originally it was probably a darker shade than contemporary notions of it, as it was first likened to Tyrian purple which is much darker. The first mauve dye was replaced with other synthetic dyes in 1873: a lighter, less-saturated shade that we are familiar with today. As Wikipedia succinctly describes it, ‘mauve contains more grey and more blue than a pale tint of magenta’.

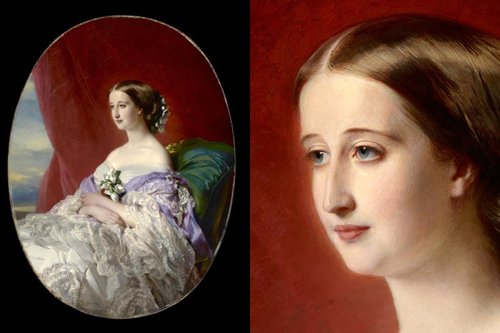

Three shades of mallow flowersHowever, while it was a synthetic dye, in the 1850s it was still quite expensive to process, and if not for Empress Eugénie, wife of Napoleon III, taking a liking to it because it supposedly exactly matched her ‘violet’ eyes, the colour might have disappeared. Queen Victoria subsequently gave it the thumbs-up, and for a time it was all the rage, reaching its heights of popularity in the 1890s.

Three shades of mallow flowersHowever, while it was a synthetic dye, in the 1850s it was still quite expensive to process, and if not for Empress Eugénie, wife of Napoleon III, taking a liking to it because it supposedly exactly matched her ‘violet’ eyes, the colour might have disappeared. Queen Victoria subsequently gave it the thumbs-up, and for a time it was all the rage, reaching its heights of popularity in the 1890s.

… for a time it was all the rage, reaching its heights of popularity in the 1890s

As with many trends, however, it soon reached over-saturation in the market and eventually it became passé, synonymous with ladies of a certain age. Even in the twentieth century, it was associated with aging, as it was one of the shades white-haired ladies chose to rinse their hair with to remove unlikable yellowish tones. Today of course that trend has been turned on its head and grey hair tinted with pastel shades is all the rage with young people!

Empress Eugenie, 1854, by Franz Xaver Winterhalter – Franz clearly thought, "Pfft, purple eyes, MY EYE!"

Empress Eugenie, 1854, by Franz Xaver Winterhalter – Franz clearly thought, "Pfft, purple eyes, MY EYE!"

Wait, what about the purple eyes?

I was interested in this notion of the Empress’s supposed violet eyes, and some research lead me to learn that Elizabeth Taylor was another celebrity famed for her violet eyes. Paintings are not necessarily true to life, and photographic evidence is obviously unreliable as it is too easy to digitally enhance hues or use colour filters in-camera.

Elizabeth Taylor in 1960 (ph unknown) and 1985 (ph Helmut Newton); she definitely seems to have naturally blue eyes that have been enhanced by the colour processing in the first photoAfter a lot of reading, I can state definitely that the human eye does not naturally come in shades of purple; ie people cannot be born with it. Put simply, the colour of an iris changes depending on how much light reaches it, and can be enhanced by coloured clothing or makeup surrounding the eyes; both Empress Eugénie and Elizabeth Taylor had blue eyes: one wore purple garments, the other purple eyeshadow. [See Further Reading below]

Elizabeth Taylor in 1960 (ph unknown) and 1985 (ph Helmut Newton); she definitely seems to have naturally blue eyes that have been enhanced by the colour processing in the first photoAfter a lot of reading, I can state definitely that the human eye does not naturally come in shades of purple; ie people cannot be born with it. Put simply, the colour of an iris changes depending on how much light reaches it, and can be enhanced by coloured clothing or makeup surrounding the eyes; both Empress Eugénie and Elizabeth Taylor had blue eyes: one wore purple garments, the other purple eyeshadow. [See Further Reading below]

Back to fashion …

Since my original story, I have since found new mauve items in differing shades all from thrift stores: a merino wool jumper, a prettily hand-knitted vintage wool cape, and a vintage angora, pearl-beaded beret. The jumper is modern, but I am not sure of the age of the latter two; the beret was missing pearls when I bought it, but the cape is pristine and could be a modern knit made using a vintage pattern. My printed velvet pants are modern, by the Australian label Charlie Brown.

Scroll down and check out some more mauve outfits from the Victorian era to the present.

Further Reading

The biology behind eye colour in humans

Were Elizabeth Taylor’s eyes really violet?

But wait, Liz Taylor had double eyelashes!

Just how did Lizzie make her blue eyes look purple?

Photos: August 2019

Victorian walking dress, 1896

Victorian walking dress, 1896 Victorian evening dress, 1896

Victorian evening dress, 1896 Victorian silk striped walking dress

Victorian silk striped walking dress Silk taffeta evening dress, 1860-1865

Silk taffeta evening dress, 1860-1865 1930s fur jacket (sold)

1930s fur jacket (sold) 1930s bias gown (for sale)

1930s bias gown (for sale) 1940s catalogue – how I would love to buy this set, especially at those prices!

1940s catalogue – how I would love to buy this set, especially at those prices! Model Evelyn Tripp, wearing a dress and matching hat, ph Frances McLaughlin-Gill for Vogue

Model Evelyn Tripp, wearing a dress and matching hat, ph Frances McLaughlin-Gill for Vogue Modern outfit

Modern outfit Rosie tote in mauve

Rosie tote in mauve

The Luxury Hat

Felt is an ancient fabric, and perhaps the first made by man: it is made rather easily as it is not woven and does not require a loom. According to legend, in the Middle Ages a wandering monk named St Clement – destined to become the fourth bishop of Rome – happened upon the process of felt-making quite by accident. It is said that to make his shoes more comfortable, he stuffed them with tow (short flax or linen fibres). Walking in them on damp ground, he discovered that his own weight and sweaty feet had matted the tow fibres together into a kind of cloth. After being made bishop (with the power to indulge his whimsy), he set up a workshop to develop felting production … and thus he became the patron saint for hatmakers, who of course use felt to this day.

Felt is an ancient fabric, and perhaps the first made by man: it is made rather easily as it is not woven and does not require a loom. According to legend, in the Middle Ages a wandering monk named St Clement – destined to become the fourth bishop of Rome – happened upon the process of felt-making quite by accident. It is said that to make his shoes more comfortable, he stuffed them with tow (short flax or linen fibres). Walking in them on damp ground, he discovered that his own weight and sweaty feet had matted the tow fibres together into a kind of cloth. After being made bishop (with the power to indulge his whimsy), he set up a workshop to develop felting production … and thus he became the patron saint for hatmakers, who of course use felt to this day.

Parisian costume, 1826

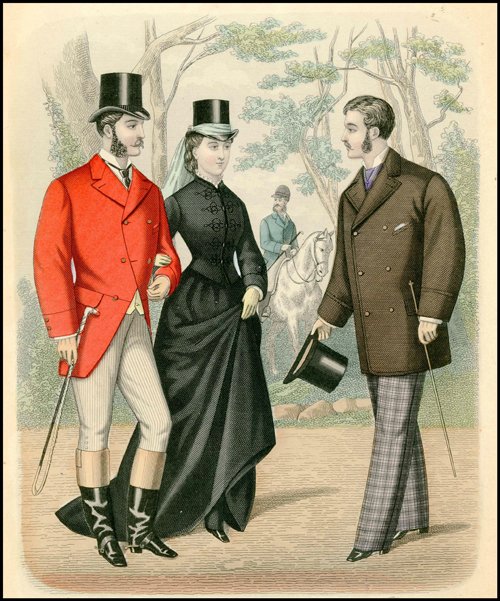

Parisian costume, 1826 Men and women’s beaver top hats, Gentleman’s Magazine of Fashion, 1876Today most felt is made of wool, but in the past, animal fur was used to make a high-quality felt. Animal fur has tiny, microscopic spines which lock together much like Velcro when heat and moisture are applied. Beaver was the superior fur because its spines were prominent and helped produce a high-quality felt; hats made from it date back to at least the sixteenth century, and they were a staggeringly expensive luxury item. Naturally, to reduce the cost of fur felt, other furs were used such as rabbit or hare, camel, and angora (mohair).

Men and women’s beaver top hats, Gentleman’s Magazine of Fashion, 1876Today most felt is made of wool, but in the past, animal fur was used to make a high-quality felt. Animal fur has tiny, microscopic spines which lock together much like Velcro when heat and moisture are applied. Beaver was the superior fur because its spines were prominent and helped produce a high-quality felt; hats made from it date back to at least the sixteenth century, and they were a staggeringly expensive luxury item. Naturally, to reduce the cost of fur felt, other furs were used such as rabbit or hare, camel, and angora (mohair).

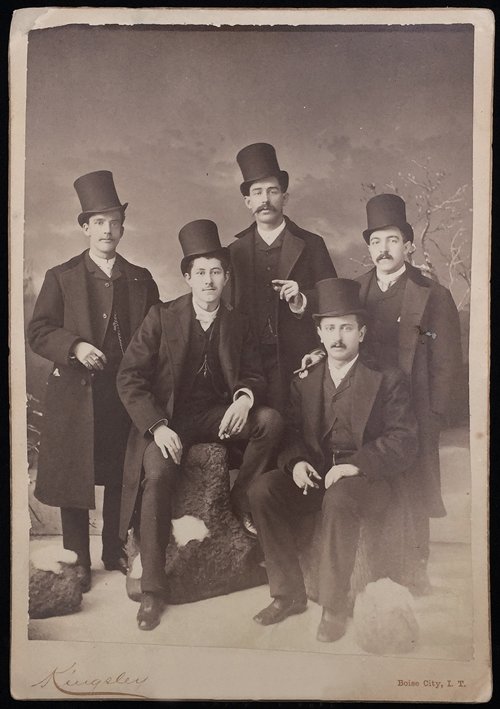

Men wearing beaver hats, 1886But it was another type of hat altogether that toppled the beaver from its luxury perch at last: the silk top hat. First invented in 1797 and scandalising the general public with its fearsome appearance, by the mid nineteenth century, the silk top hat cost half the price of beaver, and overtook it in popularity owing to changes in lifestyle which meant the hardy fur felt hats were not needed.

Men wearing beaver hats, 1886But it was another type of hat altogether that toppled the beaver from its luxury perch at last: the silk top hat. First invented in 1797 and scandalising the general public with its fearsome appearance, by the mid nineteenth century, the silk top hat cost half the price of beaver, and overtook it in popularity owing to changes in lifestyle which meant the hardy fur felt hats were not needed.

50s hat of angora fur felt; authorised reproduction of a Claude Saint-Cyr designI was initially attracted to this red 1950s pixie hat because of its dramatic shape, and the pearls (which I love) sewn all over it. It is made with Melusine, a felt made from rabbit fur. Melusine has long, fine fibres that are brushed to create a silky long-haired finish. In the past I had presumed ‘fur felt’ was a misnomer, and that such fabric was actually made from wool to look like fur. I was a bit sad when I realised this hat was real rabbit fur; however, at least it is vintage and recycled.

50s hat of angora fur felt; authorised reproduction of a Claude Saint-Cyr designI was initially attracted to this red 1950s pixie hat because of its dramatic shape, and the pearls (which I love) sewn all over it. It is made with Melusine, a felt made from rabbit fur. Melusine has long, fine fibres that are brushed to create a silky long-haired finish. In the past I had presumed ‘fur felt’ was a misnomer, and that such fabric was actually made from wool to look like fur. I was a bit sad when I realised this hat was real rabbit fur; however, at least it is vintage and recycled.

An amazing pink fur felt reproduction Regency hat, by Jane Walton, 2019I have a few other vintage hats also made from melusine, all from the 50s and 60s. While wool felt is certainly more common these days, you can still buy new fur felt hats (some sources nebulously state the fur is a ‘by-product’) – even top hats made from beaver that are worn by top cats at Ascot – and they are still quite expensive.

An amazing pink fur felt reproduction Regency hat, by Jane Walton, 2019I have a few other vintage hats also made from melusine, all from the 50s and 60s. While wool felt is certainly more common these days, you can still buy new fur felt hats (some sources nebulously state the fur is a ‘by-product’) – even top hats made from beaver that are worn by top cats at Ascot – and they are still quite expensive.

Photo: June 2019

Walking Papers

When I was in my late teens I started to wear broad-brimmed hats in summer for protection from the sun simply because I loathed the stickiness of sunscreen and decided I would only put up with it at the beach. From sun hats to parasols was a small step, and I began to collect parasols – because if a hat gave you some protection from the sun, how much more a parasol? (And from summer hats to their winter counterparts was a small leap, and thus a lifetime love affair with hats was born.)

When I was in my late teens I started to wear broad-brimmed hats in summer for protection from the sun simply because I loathed the stickiness of sunscreen and decided I would only put up with it at the beach. From sun hats to parasols was a small step, and I began to collect parasols – because if a hat gave you some protection from the sun, how much more a parasol? (And from summer hats to their winter counterparts was a small leap, and thus a lifetime love affair with hats was born.)

The first proper parasols I found were Chinese and Japanese oiled and plain paper parasols in thrift stores. They were not something I found often, but when I did they were usually inexpensive: under $10, some even under $5. The most recent acquisitions are the two that I am carrying in these pictures. I was thrilled with the flower-shaped one (possibly a Japanese one, with its cherry blossom painting), and the small one I deemed was very convenient to carry in my tote. And since I took this photo, I have found yet another – a green paper parasol.

I did see one oiled paper umbrella once which was priced around $20, but since it wasn’t significantly different to the ones I owned already, I passed on it. A quick look on Etsy ascertains that $20 is a very low price; there are many for $80 or more.*

I always assumed that the coated paper parasols were lacquered, but in fact they are oiled to make them waterproof. As the oiled paper ages it becomes rigid, and easier to break, but with sufficient care one should last for 20 years. I suspect mine are past their use-by date and won’t test them out in the rain, although I’d love to!

I always assumed that the coated paper parasols were lacquered, but in fact they are oiled to make them waterproof. As the oiled paper ages it becomes rigid, and easier to break, but with sufficient care one should last for 20 years. I suspect mine are past their use-by date and won’t test them out in the rain, although I’d love to!

Japanese family group, 1920s. (Image found on Pinterest; no original source linked.)

Japanese family group, 1920s. (Image found on Pinterest; no original source linked.) Kyoto 1955, by Kansuke YamamotoAccording to Wikipedia, the oiled paper umbrella originated in China, and spread to Korea and Japan during the Tang dynasty (7th–10th centuries). Early umbrella materials were mostly feathers or silks and only later were they covered in paper; it’s unknown when the oiled paper umbrellas were invented. You can read an interesting history about the Japanese wagasa (umbrella) and how they are painstakingly created by hand here. It’s not surprising to learn that the craft has dwindled after WWII, when synthetic umbrellas made their way to Japan. Today production of handmade wagasa is very limited.

Kyoto 1955, by Kansuke YamamotoAccording to Wikipedia, the oiled paper umbrella originated in China, and spread to Korea and Japan during the Tang dynasty (7th–10th centuries). Early umbrella materials were mostly feathers or silks and only later were they covered in paper; it’s unknown when the oiled paper umbrellas were invented. You can read an interesting history about the Japanese wagasa (umbrella) and how they are painstakingly created by hand here. It’s not surprising to learn that the craft has dwindled after WWII, when synthetic umbrellas made their way to Japan. Today production of handmade wagasa is very limited.

If I ever go to China again, or to Japan, a new one will definitely be on my list of desirable souvenirs. I wonder if anyone makes feather ones? What a fashion statement that would be – something else to add to my list of Holy Fashion Grails!

Parasols on the beach, 1920s; click through to the link and scroll to the very bottom of the page to read more about beach parasols in this era.

Parasols on the beach, 1920s; click through to the link and scroll to the very bottom of the page to read more about beach parasols in this era. A lovely modern image of a woman with an umbrella in the snow

A lovely modern image of a woman with an umbrella in the snow

Fashion Notes

I am wearing a classic Chinese-style silk blouse with mandarin collar and frog fastenings by Sarah-Jane, which I found in a thrift store in country Victoria; the pants are modern, by a French label bought online. My bangles, ring and earrings are cloisonné, also found in thrift stores; the technique of cloisonné had spread to China by the 13–14th centuries where it became hugely popular; to the present day it is one of the world’s best known enamel cloisonné. The fabric necklace of insects and flowers was a souvenir from Hang Nga Guesthouse, popularly known as “Crazy House” for its architecture in Da Lat, Vietnam, and likewise, the beaded and embroidered slippers are a Vietnamese souvenir, bought in the main market in Saigon.

*All prices in Australian dollars

Photos: March 2018

Feathered Fantasies

Models at the Hippodrome de Longchamp, showing off scandalous new gowns showcasing the S-line (and their figures), and enormous hats of course, Paris 1908During the Edwardian period, the ideal image of womanhood was to look fragile and delicate, and the fashion was for the flattering S-line, with long luxurious hair piled high to show off slim necks. Enormous hats fantastically trimmed were the crown of these ensembles, designed to complement and set off the feminine silhouette.

Models at the Hippodrome de Longchamp, showing off scandalous new gowns showcasing the S-line (and their figures), and enormous hats of course, Paris 1908During the Edwardian period, the ideal image of womanhood was to look fragile and delicate, and the fashion was for the flattering S-line, with long luxurious hair piled high to show off slim necks. Enormous hats fantastically trimmed were the crown of these ensembles, designed to complement and set off the feminine silhouette.

The years of the Edwardian British period covers the short reign of King Edward VII, 1901 to 1910, although sometimes it includes the years up to WWI. At this time, hats were a crucial part of the dress code for people from all walks of life, young or old, rich or poor. There were different hats acceptable for each strata of society – but all wore hats, all the time. Women changed their hats with their outfits several times a day and would never step out tête-nue (with a bare head) – that was considered a huge social solecism. It was acceptable only for beggars to be hatless.

1909

1909

A lady and an assistant settle down to the pleasures of selecting and decorating a stylishly large hat from the befeathered and beribboned collection available at the Paquin couture house millinery rooms, 1909. From ‘The Golden Age of Style’ by Julian Robinson, Orbis Publishing 1976Milliners could and did go to town, extravagantly decorating these wide picture hats with silks and velvets, ribbons and artificial flowers, and after the death of Queen Victoria, bright colours becamse hugely fashionable. The most popular millinery trim of all were feathers, for throughout history, plumes on hats have been a sign of status and wealth. The rich of this time were no exception – some of the hats were insanely huge, even obscenely ostentatious.

A lady and an assistant settle down to the pleasures of selecting and decorating a stylishly large hat from the befeathered and beribboned collection available at the Paquin couture house millinery rooms, 1909. From ‘The Golden Age of Style’ by Julian Robinson, Orbis Publishing 1976Milliners could and did go to town, extravagantly decorating these wide picture hats with silks and velvets, ribbons and artificial flowers, and after the death of Queen Victoria, bright colours becamse hugely fashionable. The most popular millinery trim of all were feathers, for throughout history, plumes on hats have been a sign of status and wealth. The rich of this time were no exception – some of the hats were insanely huge, even obscenely ostentatious.

Feathers of all kinds were fashioned by the 800 plumassiers in Paris that employed around 7000 people. Anything from little spiky trimmings to boas, tufts and sprays of feathers called aigrettes were cut, dyed and arranged from a wide variety of feathers: cockerel, pheasant, marabou, ostrich, ospreys, herons or birds of paradise. Sometimes even whole stuffed birds perched atop these monstrosities.

Bird of paradiseSuch decorations were extremely expensive; a hat trimmed with natural bird of paradise plumes could fetch a price of $100, a fortune in those days – that is over AU$4,400 or US$3,045 in today’s values. (For comparison I spotted a YSL black rabbit fur felt hat on Farfetch for over $3000 – it does have an elegant shape and details, for example tasselled ties, but that seems laughably overpriced for a comparatively unexciting hat made of inexpensive materials.)

Bird of paradiseSuch decorations were extremely expensive; a hat trimmed with natural bird of paradise plumes could fetch a price of $100, a fortune in those days – that is over AU$4,400 or US$3,045 in today’s values. (For comparison I spotted a YSL black rabbit fur felt hat on Farfetch for over $3000 – it does have an elegant shape and details, for example tasselled ties, but that seems laughably overpriced for a comparatively unexciting hat made of inexpensive materials.)

The feathers of the Roseate spoonbill are so gorgeous they almost lead them to extinctionAnother bird that was hunted almost to extinction is the roseate spoonbill – in the late nineteenth century its feathers were literally worth more than gold – $32 per ounce, compared with $20 for gold. [al.com] Their almost total disappearance was one of the factors that lead to the formation of the Audobon Society, dedicated to conservation, eventually leading to the banning of the usage of feathers from endangered species.

The feathers of the Roseate spoonbill are so gorgeous they almost lead them to extinctionAnother bird that was hunted almost to extinction is the roseate spoonbill – in the late nineteenth century its feathers were literally worth more than gold – $32 per ounce, compared with $20 for gold. [al.com] Their almost total disappearance was one of the factors that lead to the formation of the Audobon Society, dedicated to conservation, eventually leading to the banning of the usage of feathers from endangered species.

Fashions at Longchamp

Fashions at Longchamp Fashion from Paris – Les Modes February 1907

Fashion from Paris – Les Modes February 1907 c. 1912

c. 1912 Jane Renouardt

Jane Renouardt c. 1900 The Bonita Hat – Huge oblong circle shape made of black plush with flamboyant turquoise lining that shows. It is trimmed with black and turquoise ostrich plumes. There is a turquoise and purple ribbon and velour 'grapes' on the ribbon. Originally sold on Ruby Lane.Three out of four hats featured feathers or whole birds, such was the popularity of plumage in the Victorian and Edwardian eras. Today, feathers are still popular of course, but milliners have become more creative with the feathers from farmed ostriches, pheasants, ducks and cockerels.

c. 1900 The Bonita Hat – Huge oblong circle shape made of black plush with flamboyant turquoise lining that shows. It is trimmed with black and turquoise ostrich plumes. There is a turquoise and purple ribbon and velour 'grapes' on the ribbon. Originally sold on Ruby Lane.Three out of four hats featured feathers or whole birds, such was the popularity of plumage in the Victorian and Edwardian eras. Today, feathers are still popular of course, but milliners have become more creative with the feathers from farmed ostriches, pheasants, ducks and cockerels.

During the militant phase of the Suffragettes and Blue Stockings around 1908, fashion began to simplify, and while hats were still de rigeur, they too fell in line with Reform fashions, for not even Suffragettes would cease wearing hats entirely – they were reluctant to outrage the establishment so utterly. Huge bows in sumptuous fabrics became more favoured for trimming, with the first cloches appearing in 1917, heralding the way for a vastly different style of hat in the 1920s.

Simpler hats of the latter Edwardian years, top right 1910, all others 1912

Simpler hats of the latter Edwardian years, top right 1910, all others 1912 Hat featuring a fabulously huge bow, Ladies Home Journal, 1910

Hat featuring a fabulously huge bow, Ladies Home Journal, 1910

Photos: Vintage images found on Pinterest; I have tried to include information and original links where available.

Additional reference: The Century of Hats, Susie Hopkins, Chartwell Books 1999