Alice’s Adventures on Film

Tatiana's adventures inside a sandwich boardOne of my favourite childhood books was Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland. So I was very much looking forward to seeing the Wonderland exhibition at the Australian Centre of the Moving Image (ACMI), which explores the many adventures of Carroll’s famous story on film.

Tatiana's adventures inside a sandwich boardOne of my favourite childhood books was Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland. So I was very much looking forward to seeing the Wonderland exhibition at the Australian Centre of the Moving Image (ACMI), which explores the many adventures of Carroll’s famous story on film.

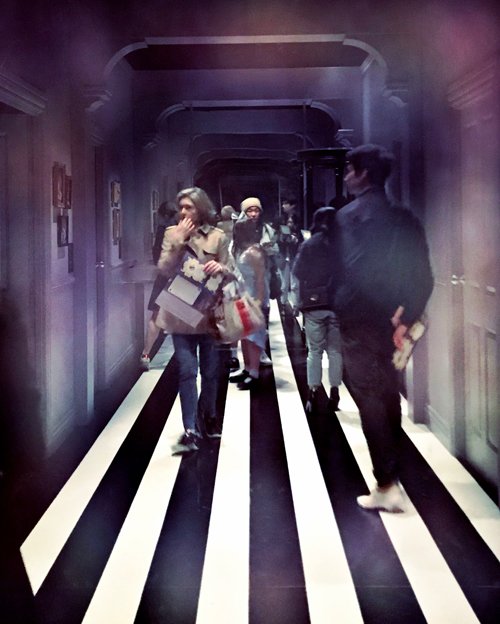

The disorienting mirrored Hallway of Doors

The disorienting mirrored Hallway of Doors Looking through the two-way mirror into the Hallway of DoorsBeginning with the Hallway of Doors (enter by the smallest door, no matter how old you are), is a series of fantastical rooms, with names such as ‘The Pool of Tears’, ‘Looking Glass House’ and ‘A Mad Tea Party’. On show is charming footage from the late nineteenth century to the multitude of iterations produced in the century since, as well as a plethora of other material such as Charles Dodgson’s original concept drawings, magic lantern projections, vintage posters, animation cels, puppets, props and costumes.

Looking through the two-way mirror into the Hallway of DoorsBeginning with the Hallway of Doors (enter by the smallest door, no matter how old you are), is a series of fantastical rooms, with names such as ‘The Pool of Tears’, ‘Looking Glass House’ and ‘A Mad Tea Party’. On show is charming footage from the late nineteenth century to the multitude of iterations produced in the century since, as well as a plethora of other material such as Charles Dodgson’s original concept drawings, magic lantern projections, vintage posters, animation cels, puppets, props and costumes.

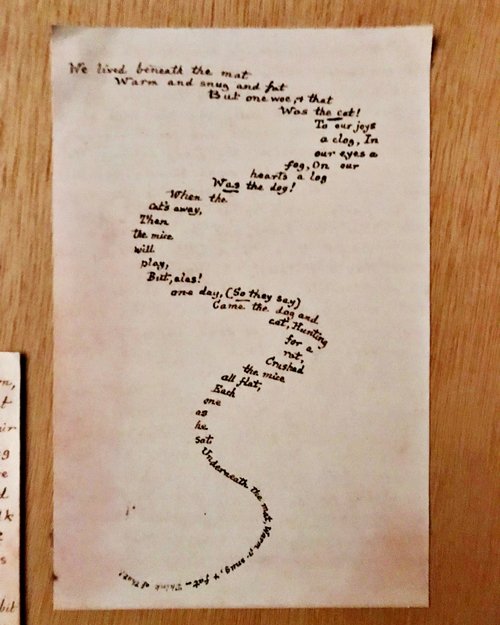

This was always my favourite page in the book when I was very little, so I was thrilled to see Charles Dodgson's original drawing, c1862–64The exhibition is immersive from the get go. On entrance, each attendee is given an ‘enchanted Lost Map of Wonderland’ that unlocks additional surprises with the aid of digital scanners in different rooms of the exhibition – if you could get past the kids hovering over the scanners.

This was always my favourite page in the book when I was very little, so I was thrilled to see Charles Dodgson's original drawing, c1862–64The exhibition is immersive from the get go. On entrance, each attendee is given an ‘enchanted Lost Map of Wonderland’ that unlocks additional surprises with the aid of digital scanners in different rooms of the exhibition – if you could get past the kids hovering over the scanners.

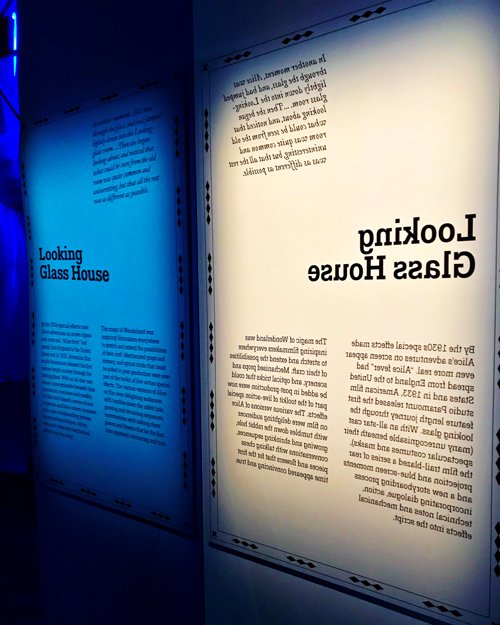

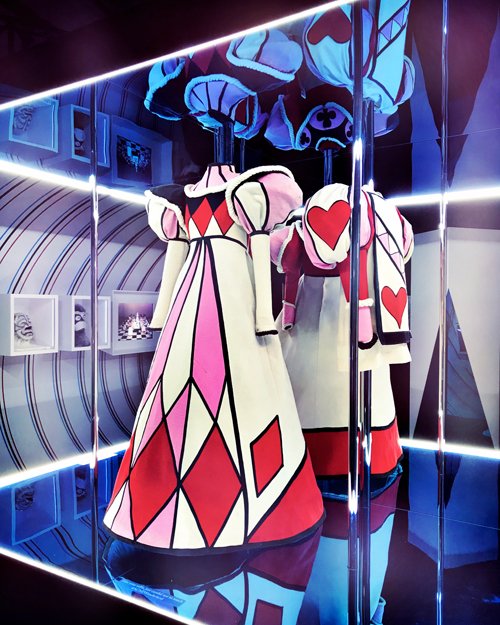

Looking Glass House; the exhibition's curation is thoughtful and thorough, and the design is clever and entertaining for young and old

Looking Glass House; the exhibition's curation is thoughtful and thorough, and the design is clever and entertaining for young and old  Queen's costumes in Looking Glass HouseThere are also several video installations, and my favourite was at the end, a montage of footage from film, television and advertising showcasing how the story of Alice has entered and utterly saturated popular culture to the present day. I could not help picturing how astonished and gratified Dodgson would be if he could see how far in time and space his story has reached.

Queen's costumes in Looking Glass HouseThere are also several video installations, and my favourite was at the end, a montage of footage from film, television and advertising showcasing how the story of Alice has entered and utterly saturated popular culture to the present day. I could not help picturing how astonished and gratified Dodgson would be if he could see how far in time and space his story has reached.

If you are in Melbourne, the exhibition is running at ACMI every day of the week until 7 October, and is a must-see.

Clocks

Clocks Inside the video installation of A Mad Hatter's Tea Party

Inside the video installation of A Mad Hatter's Tea Party Inside the video installation of A Mad Hatter's Tea Party

Inside the video installation of A Mad Hatter's Tea Party

A Film Spectrum

I am feeling very pleased with myself in my progress with one of my New Year’s resolutions: I vowed to make an effort to see more films this year (in the cinema, rather than on DVD). So far I have seen three in January: The Punk Singer, Her, and Saving Mr Banks – three films that are all very different from one another.

I am feeling very pleased with myself in my progress with one of my New Year’s resolutions: I vowed to make an effort to see more films this year (in the cinema, rather than on DVD). So far I have seen three in January: The Punk Singer, Her, and Saving Mr Banks – three films that are all very different from one another.

The first I saw by accident, but the ridiculous concatenation of circumstances involved in this accident indicate that I was fated to see it. I was in fact meant to see the French film Rust and Bone (also apparently very good). But a series of fortunate events (broken down trams, last-minute cab rides, an out-of-place private party, a closing-down cinema, bad signage, a misplaced ticket and a blasé usher) lead me to feel I had fallen down the rabbit-hole, groping around for a seat in a dark cinema and bemusedly watching The Punk Singer.

a series of fortunate events … lead me to feel I had fallen down the rabbit-hole

The Punk Singer

I have never been into punk music and know little about the scene, but this did not stop my fascination and very real enjoyment in this documentary directed by Sini Anderson, about Kathleen Hanna, lead singer of punk band Bikini Kill and dance-punk trio Le Tigre. A passionate and outspoken firebrand, Hanna reluctantly took on the mantle of figurehead of the riot grrrl movement, becoming an icon of the feminist movement amongst a new generation of women. She was a force to be reckoned with, but suddenly, in 2005, she faded from the music scene. The documentary accounts for two decades of her life through archival footage and intimate interviews with Hanna and many others in the industry, and is truly engrossing and inspiring.

Her

A strange combination of sci-fi and rom-com, Spike Jonze’s Her was simply a fun night at the movies. I was initially very dubious about the premise, that of a man (Joaquin Phoenix) who falls in love with his computer operating system (seductively voiced by Scarlett Johansson). It was a difficult concept to believe, but sometimes those stories – if they’re done right – can be the most interesting. Her was.

A strange combination of sci-fi and rom-com, Spike Jonze’s Her was simply a fun night at the movies. I was initially very dubious about the premise, that of a man (Joaquin Phoenix) who falls in love with his computer operating system (seductively voiced by Scarlett Johansson). It was a difficult concept to believe, but sometimes those stories – if they’re done right – can be the most interesting. Her was.

Filmed beautifully, the science fiction world Jonze created is not so far from our future as to seem fantastical; rather, the technology (and the psychology behind the people using it) is entirely believable and convincing. Although I found the dénouement absolutely right, I thought the very final scene unnecessarily ambiguous, and a little too smugly clever. Still, a thought-provoking and very good film, especially for its genre. Also, the men’s fashion is worth a good giggle. I can only hope I will start seeing it on the streets soon!

I have two words for you: Harry and High-Pants. Click image to read more about the costuming of Her.

I have two words for you: Harry and High-Pants. Click image to read more about the costuming of Her.

I am not a Tom Hanks fan at all. Never have been. I am proud to say I still have not seen Forrest Gump (except bits of it I caught in my peripheral vision while seated sideways – so as not to inadvertently glance at the tv – and couldn’t drown out with my walkman when I was once trapped on an interstate coach between Merimbula and Melbourne). I have managed to avoid Philadelphia, Saving Private Ryan, The Green Mile and all the other schmaltzy propaganda he has been involved in. Nor was I ever particularly into Mary Poppins, but I do like Emma Thompson.

I am not a Tom Hanks fan at all. Never have been. I am proud to say I still have not seen Forrest Gump (except bits of it I caught in my peripheral vision while seated sideways – so as not to inadvertently glance at the tv – and couldn’t drown out with my walkman when I was once trapped on an interstate coach between Merimbula and Melbourne). I have managed to avoid Philadelphia, Saving Private Ryan, The Green Mile and all the other schmaltzy propaganda he has been involved in. Nor was I ever particularly into Mary Poppins, but I do like Emma Thompson.

Saving Mr Banks

When I first saw the trailer for Saving Mr Banks, directed by John Lee Hancock, I was caught by surprise. I knew nothing of this story at all, or about PL Travers, and very little about Walt Disney, but the trailer caught my attention … It was obviously a good one, considering my avowed dislike of Hanks’ film history! A fictionalised recounting of PL Travers’ life, the author of the Mary Poppins books, and the story of how it came to be produced by Disney is truly interesting. It takes us into the processes of transforming a children’s book into a script for a musical, which is fascinating enough, but the personalities involved in the making of it add such depth and humanity.

Travers is an astonishing woman with a very forceful personality – her antics in the Disney studios made me alternately gasp and laugh. All the actors were great, playing their characters with sympathy and subtlety. I found the flashbacks to Travers’ childhood in Australia an absorbing and revealing counterpoint – Colin Farrell as Travers’ father had a wonderful rapport with his children (who else would so perfectly play the feckless Irishman?). The film is truly moving, a melding of heartbreak and hope.

The Bonus Film I Saw on DVD

And the bonus film I saw yesterday on DVD: Holy Motors. This is an arty French film written and directed by Leos Carax that was well received by many critics and audiences, although it was sold to me by a close friend as a film she and her husband hated so much they could not watch more than twenty minutes of it. She exhorted me to see it just so she could hear what I thought of it. With such accolades, how could I resist?

And the bonus film I saw yesterday on DVD: Holy Motors. This is an arty French film written and directed by Leos Carax that was well received by many critics and audiences, although it was sold to me by a close friend as a film she and her husband hated so much they could not watch more than twenty minutes of it. She exhorted me to see it just so she could hear what I thought of it. With such accolades, how could I resist?

We follow the adventures of one man (Denis Lavant) chauffeured in his limo from appointment to appointment, each more strange and inexplicable than the last. His entire character changes with each stop, he passes through death into a new life, and it is impossible to decipher what is real and what is not.

I did not hate it however. I watched it through to the end, although I occasionally found myself feeling impatient with its sense of smug arty cleverness and had a feeling of wanting it to hurry along. Both beautiful and grotesque, I found it entertaining enough, although I remain unconvinced about its world (unlike with the world of Her) – it just seemed to be trying too hard to impress its audience. Perhaps it was too grandiose, too over-the-top to draw me in – its strangeness was too gaudy. And as for the very final scene with the limos (in entirely deserving all-caps): ATROCIOUS! Silly, unnecessary, and undermining the entire film. It is natural to seek clarification, understanding; to decode and decipher the hidden clues within a film such as this, but sometimes there are no answers. What is then left? The answer should be ‘art’, but in my view, Holy Motors is a paean to style over substance. I was left feeling dissastisfied.

But Wait, There’s More!

Right off the top of my head – if we’re talking mysterious cinematic puzzles – one of my all-time favourite films is Alain Resnais’ Last Year at Marienbad. Much has been written about this controversial 1961 film that fascinated and baffled critics and audiences alike, but its characters also populate an inexplicable and shadowy world that almost defies comprehension. It is poetically shot in black and white Cinemascope, carrying the mood of a dream one can’t quite remember, and ‘is a riddle of seduction, a mercurial enigma darting between a present and past which may not even exist, let alone converge’. [Rotten Tomatoes]

Right off the top of my head – if we’re talking mysterious cinematic puzzles – one of my all-time favourite films is Alain Resnais’ Last Year at Marienbad. Much has been written about this controversial 1961 film that fascinated and baffled critics and audiences alike, but its characters also populate an inexplicable and shadowy world that almost defies comprehension. It is poetically shot in black and white Cinemascope, carrying the mood of a dream one can’t quite remember, and ‘is a riddle of seduction, a mercurial enigma darting between a present and past which may not even exist, let alone converge’. [Rotten Tomatoes]

A film still of Last Year at Marienbad, with Giorgio Albertazzi and Delphine Seyrig

A film still of Last Year at Marienbad, with Giorgio Albertazzi and Delphine Seyrig

In an overblown baroque European hotel a man approaches a woman and tries to convince her they were romantically involved the year before – the woman denies it is so. Her husband is an intruder, a somewhat shadowy and sinister figure in the background. Time and space shifts along with truth and fiction to an almost indistinguishable degree. But logic has no place in this universe – it is a matter of indifference – what matters is the art of storytelling. And Resnais’ is a master – Carax cannot compare. This film holds me absolutely spellbound every time I watch it.

Delphine Seyrig in a film still of Last Year at Marienbad

Delphine Seyrig in a film still of Last Year at Marienbad

Wings: A Review

On Saturday I noticed by chance on Facebook that the Astor Theatre was showing a rare print of the 1927 film Wings, starring Clara Bow, with Charles ‘Buddy’ Rogers, and Richard Arlen. Gary Cooper appears in a role which helped launch his career in Hollywood and also marked the beginning of his affair with Clara Bow. [Wikipedia]

On Saturday I noticed by chance on Facebook that the Astor Theatre was showing a rare print of the 1927 film Wings, starring Clara Bow, with Charles ‘Buddy’ Rogers, and Richard Arlen. Gary Cooper appears in a role which helped launch his career in Hollywood and also marked the beginning of his affair with Clara Bow. [Wikipedia]

Originally released by Paramount Pictures, the film is a silent action film about World War 1 aviator pilot friends, and as Clara Bow stated, “Wings is … a man's picture and I’m just the whipped cream on top of the pie”. This is unfortunately true, but she is a delicious addition to the recipe.

Charles ‘Buddy’ Rogers, Clara Bow and Richard Arlen

Charles ‘Buddy’ Rogers, Clara Bow and Richard Arlen It is the cinematography and aviation scenes that are the real stars in this film however. A number of the cast and crew had all served in WW1 as military aviators, so they were able to draw on this experience in the execution of these scenes. What makes it much more moving and suspenseful than modern films about WW1 is this fact: the war had ended only ten years earlier, and this brings such immediacy and verisimilitude to the action. There is also real footage from WW1 mixed in – creating a strange juxtaposition considering Wings is a fictionalised account. Watching it one is made soberly aware that some of these men are actually dying.

It is the cinematography and aviation scenes that are the real stars in this film however. A number of the cast and crew had all served in WW1 as military aviators, so they were able to draw on this experience in the execution of these scenes. What makes it much more moving and suspenseful than modern films about WW1 is this fact: the war had ended only ten years earlier, and this brings such immediacy and verisimilitude to the action. There is also real footage from WW1 mixed in – creating a strange juxtaposition considering Wings is a fictionalised account. Watching it one is made soberly aware that some of these men are actually dying.

Albert Conti, Charles ‘Buddy’ Rogers, Richard Arlen

Albert Conti, Charles ‘Buddy’ Rogers, Richard Arlen Charles ‘Buddy’ Rogers; I was pleased to see some boxing action while the boys were at aviation training

Charles ‘Buddy’ Rogers; I was pleased to see some boxing action while the boys were at aviation training

Wings went on to win the first Academy Award for Best Picture, but the film was unfortunately subsequently lost – until it was found in the Cinémathèque Française film archive and was copied from nitrate film to safety film stock. The film was meticulously restored and released by Paramount on DVD in 2012, and the musical score was re-orchestrated.

The sound effects were recreated at Skywalker Sound using archived audio tracks – although of course there was no voice, the sound of motors and engines interspersed through the film added greatly to the dramatic tension created by the score. It is easy too to forget that silent films were not all necessarily purely black and white: Wings was colour tinted in sepia and cyanotype tones, as well as black. The scenes using the Handschiegl color process to give colour to explosions were also recreated for the restored version. [Wikipedia]

Charles ‘Buddy’ Rogers and Clara Bow in the Folies Bergère and some bubble actionWatching the scenes set in Paris was fascinating from a cultural point of view, glimpsing the people in the streets – how they dressed, spoke (or gesticulated animatedly) and behaved – and of course the fashion was especially enjoyable for me. I loved the way Clara Bow wore her scarf: tied in a bow around her neck, and then tucked into her belt. (One to try at home!) And her uniform as an ambulance driver in the war was wonderful – those lace-up knee-high boots were fabulous. There was also a fantastic comic scene involving drunken behaviour and hallucinatory bubbles in the Folies Bergère, where Clara Bow came into her own (watch her shimmy here). And let’s not forget the male nudity, the first scenes where men kissed on screen, and a brief glimpse of Clara Bow’s breasts (which I missed).

Charles ‘Buddy’ Rogers and Clara Bow in the Folies Bergère and some bubble actionWatching the scenes set in Paris was fascinating from a cultural point of view, glimpsing the people in the streets – how they dressed, spoke (or gesticulated animatedly) and behaved – and of course the fashion was especially enjoyable for me. I loved the way Clara Bow wore her scarf: tied in a bow around her neck, and then tucked into her belt. (One to try at home!) And her uniform as an ambulance driver in the war was wonderful – those lace-up knee-high boots were fabulous. There was also a fantastic comic scene involving drunken behaviour and hallucinatory bubbles in the Folies Bergère, where Clara Bow came into her own (watch her shimmy here). And let’s not forget the male nudity, the first scenes where men kissed on screen, and a brief glimpse of Clara Bow’s breasts (which I missed).

Twenties scarf action with Clara Bow in the back yard

Twenties scarf action with Clara Bow in the back yard Clara Bow in her ambulance driver’s uniform – check out those boots!On a final note, here’s an interesting piece of trivia: Wings was the only silent movie to win an Oscar for Best Picture – until the experimental film The Artist came along in 2011.

Clara Bow in her ambulance driver’s uniform – check out those boots!On a final note, here’s an interesting piece of trivia: Wings was the only silent movie to win an Oscar for Best Picture – until the experimental film The Artist came along in 2011.

Watch the film on DVD if you can, but it really should be seen on the big screen. Thank you Astor.

Read more here.

Charles ‘Buddy’ Rogers and Clara Bow

Charles ‘Buddy’ Rogers and Clara Bow

The Great Gatsby: Character vs Caricature

The decadent and hedonistic Twenties roared onto the screen in Baz Luhrman’s The Great Gatsby. It was a fabulous spectacle: all non-stop speed, dazzle and dash, bursts of colour, explosions of noise and music and frenzied partying. The fashion evoked the era but bore an unmistakably twenty-teens edge, the diamonds sparkled aggressively and the pearls provided a soft glow in counterpoint. Probably that much beading will never be seen again in the history of cinema.

The decadent and hedonistic Twenties roared onto the screen in Baz Luhrman’s The Great Gatsby. It was a fabulous spectacle: all non-stop speed, dazzle and dash, bursts of colour, explosions of noise and music and frenzied partying. The fashion evoked the era but bore an unmistakably twenty-teens edge, the diamonds sparkled aggressively and the pearls provided a soft glow in counterpoint. Probably that much beading will never be seen again in the history of cinema.

But this was a triumph of style over substance – however much I do admire Luhrman’s commitment to his singular style – for where was the heart of this story? Where was the humanity, I wondered? This is a tale of vain and empty people, perhaps a true reflection of a certain strata of society of the time, but by film’s end there was nothing left to hold onto. We do not watch real people, but larger-than-life archetypes – caricatures. We do not care if they live or die, and can only despise them for their various wants of character. But this is no fault of Luhrman’s: it is how Fitzgerald wrote his characters.

Gatsby himself is an egomaniacal crook, naïve about love and obsessed with the spineless and mercenary child, Daisy (even her name is unsophisticated); her husband Tom, a lusty, cruel and hypocritical brute takes advantage of his discontented mistress and her hapless husband; the extremely well-dressed and polished Jordan is the kindest but ultimately wrapped up in herself; and finally Nick, our narrator, is an ineffectual observer who is swept along this fast current and laments too late.

But the film is spectacular to look at – everyone and everything is beautiful. The Great Gatsby is super-glossy, a feast for the eyes served at speed, and ultimately a wonderland that cannot be believed in. It is a modern fairy-tale with a grim conclusion.

Read an intelligent review of the book by Kathryn Schulz at Vulture.

Review: Anna Karenina

On Saturday night I saw Anna Karenina. I had heard mixed reviews and was dubious about the much-talked-about staging, but I was curious and very interested to see the result at last, albeit so late in the season. Here’s what I thought …

On Saturday night I saw Anna Karenina. I had heard mixed reviews and was dubious about the much-talked-about staging, but I was curious and very interested to see the result at last, albeit so late in the season. Here’s what I thought …

Despite my misgivings, I was immediately captured and entranced by the opening scenes. Set on a nineteenth century proscenium arch stage, with the hustle and bustle of scene-changers and characters wandering about backstage and along the precarious wooden gantries above, this is a metaphor neatly dividing Moscow and St Petersburg in their two worlds of rich and poor, of artifice and harsh reality.

It was a well-made film, beautifully filmed and edited with mostly competent performances; visually and stylistically it was quite poetic. But even as I marvelled at its cleverness, I am not sure if the Joe Wright and Tom Stoppard were successful in distilling the essence of Tolstoy's book.

It was a well-made film, beautifully filmed and edited with mostly competent performances; visually and stylistically it was quite poetic. But even as I marvelled at its cleverness, I am not sure if the Joe Wright and Tom Stoppard were successful in distilling the essence of Tolstoy's book.

I questioned some of the casting: I was never convinced Keira Knightley was the best choice for the title role, and Jude Law seemed an unusual choice as Karenin (not to mention ironically inapt). However Aron Taylor-Johnson, playing Vronsky, seemed suitably vain and effeminate, not virile at all – though Law's castrated Karenin was virtually sexless. It was certainly a subtle portrayal by Law and drew great sympathy from me, but his Karenin did no justice to Anna and very little to cast her character in a flattering light. Karenin was a hard, unsympathetic man, many years Anna’s senior, but it was difficult to see him as anything more than hard-done-by. And Knightley’s Anna, overwhelmed by love and passion, did nothing to convey the anguish she suffered at the loss of her son, the torment of fearing she would lose Vronsky (which eventually unhinged her), and the depths of humiliation she suffered at society’s rejection of her. In effect, she was shallow and rather selfish.

In Tolstoy’s book, the sweet purity of Levin and Kitty's marriage is juxtaposed against the dishonourable nature of Anna and Count Vronsky's relationship (according to the mores of the day), but I do not think this was adequately conveyed to a modern audience – if even it could be judging by the reactions of some of the patrons in the cinema the night I saw the film. One of the tenderest scenes was played out between Levin and Kitty when they reveal their love for one another using alphabet blocks – including a very cute nod to modern texting parlance with the blocks spelling ‘ily’.

In Tolstoy’s book, the sweet purity of Levin and Kitty's marriage is juxtaposed against the dishonourable nature of Anna and Count Vronsky's relationship (according to the mores of the day), but I do not think this was adequately conveyed to a modern audience – if even it could be judging by the reactions of some of the patrons in the cinema the night I saw the film. One of the tenderest scenes was played out between Levin and Kitty when they reveal their love for one another using alphabet blocks – including a very cute nod to modern texting parlance with the blocks spelling ‘ily’.

Although the stylised presentation of the story helped to truncate Tolstoy's book (and rationalise yet another production), occasionally there were jarring interludes – notably Levin's meetings with his brother – that made me wonder why they had been put in, because they were simply not adequately fleshed out.

The stage setting was utilised beautifully, from how sets were changed (backdrops, scenic art, doors opening on new scenes), to the use of space (the stage, backstage as well as the seating area), minor actors' roles seamlessly changing. The choreography and film editing was breathtaking in its perfection.

Sound – and silence – was used to great effect: clerks stamping paperwork in tune, the rapid beat of a fan in time with panicked breath and heart. The ball scene when Anna and Alexey dance for the first time was brilliantly portrayed, with Kitty changing partners as the lovers continually swirl around in the middle, deaf and blind to their surroundings – the set darkens and Anna and Vronsky dance alone in the darkness until they gradually return to the hubbub.

Sound – and silence – was used to great effect: clerks stamping paperwork in tune, the rapid beat of a fan in time with panicked breath and heart. The ball scene when Anna and Alexey dance for the first time was brilliantly portrayed, with Kitty changing partners as the lovers continually swirl around in the middle, deaf and blind to their surroundings – the set darkens and Anna and Vronsky dance alone in the darkness until they gradually return to the hubbub.

Joe Wright … has nevertheless created a a cornucopia of deilghts in this film of great beauty, rich detail and real originality.

The crowning achievement was the stylised staging of the horserace, with spectators sitting in the theatre seats before the stage, and only the sound of the horse’s hooves thundering in the darkness of ‘offstage’ hinting at reality.

The crowning achievement was the stylised staging of the horserace, with spectators sitting in the theatre seats before the stage, and only the sound of the horse’s hooves thundering in the darkness of ‘offstage’ hinting at reality.

This is a story of such scope it would be difficult for anyone to truly do it justice, and Joe Wright, though he has succeeded only in part, has nevertheless created a a cornucopia of deilghts in this film of great beauty, rich detail and real originality.