The Mystery and Melancholy of de Chirico

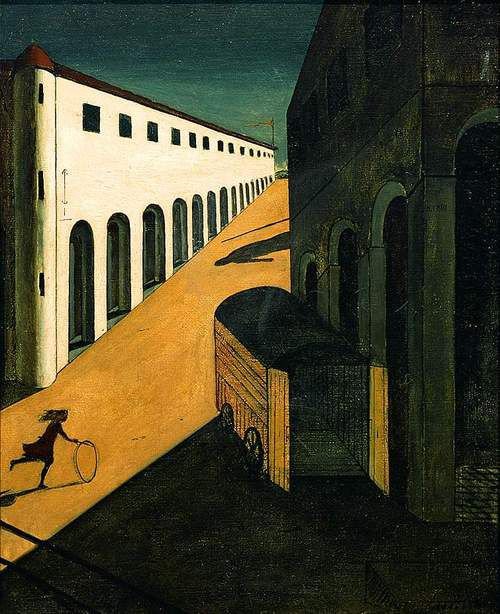

Mystery and Melancholy of a Street, 1913I am sorry to say that I never studied Metaphysical Art when I was at art school – I don’t even remember the term – but I must have been familiar with one of its founders even then, the artist Giorgio de Chirico (1888–1878), for his work has long been a favourite of mine.

Mystery and Melancholy of a Street, 1913I am sorry to say that I never studied Metaphysical Art when I was at art school – I don’t even remember the term – but I must have been familiar with one of its founders even then, the artist Giorgio de Chirico (1888–1878), for his work has long been a favourite of mine.

In Italian, Metaphysical Art translates as pittura metafisica, and de Chirico and fellow Italian painter Carlo Carrà (a leader of the Futurist movement as well) developed it in the second decade of the twentieth century. ‘Metaphysical art combined everyday reality with mythology, and evoked inexplicable moods of nostalgia, tense expectation, and estrangement.’ [Wikipedia]

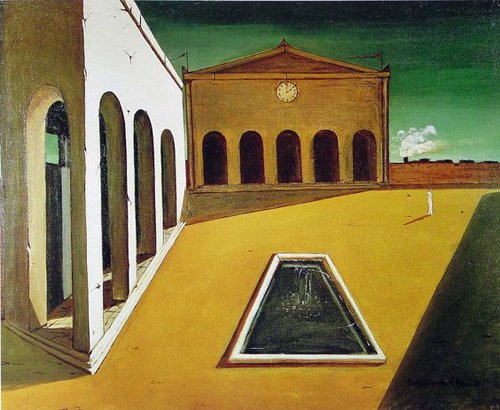

The Anguish of Departure, 1914

The Anguish of Departure, 1914

there is a disturbing and vaguely menacing mood in the dreamlike cityscapes.

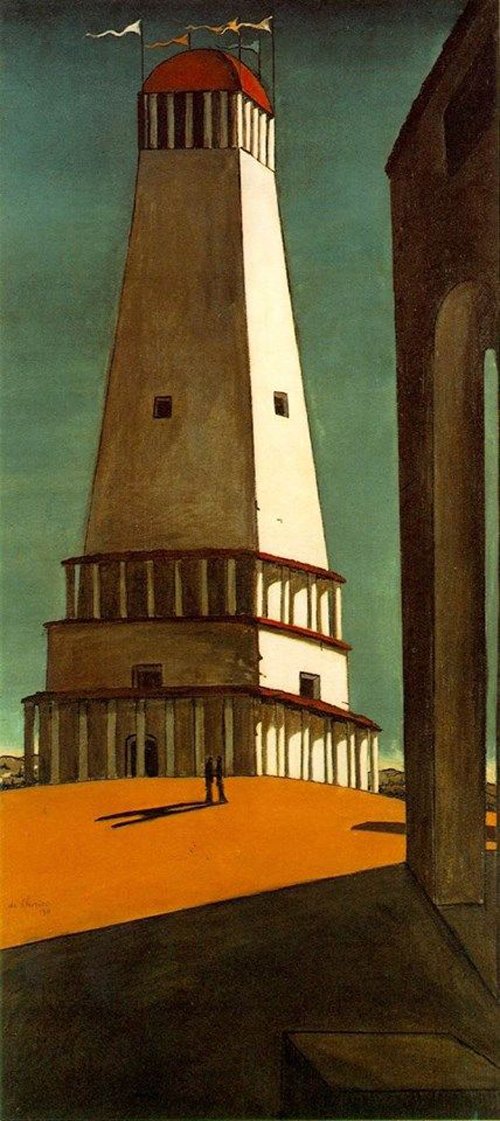

When you look at de Chirico’s Metaphysical paintings (all produced over a decade, between 1909 and 1919), not only do they certainly evoke such moods, but you are not surprised to learn that they greatly influenced the Surrealists, for there is a disturbing and vaguely menacing mood in the dreamlike cityscapes. It is an effect achieved in part through the juxtaposition of tiny figures against monumental architecture.

Delights of the Poet, 1913De Chirico was inspired by the writings of Nietzsche, ‘with its suggestions of unseen auguries beneath the appearance of things’, which translated into his own unexpected responses to quotidian surroundings and objects. He wrote in 1909 about the ‘host of strange, unknown and solitary things that can be translated into painting ... What is required above all is a pronounced sensitivity’— and both imagination and inclination I would think, to look beyond the surface of accustomed sights, such as the archways and piazzas of Turin where he spent a few days while on his way to Paris in 1911.

Delights of the Poet, 1913De Chirico was inspired by the writings of Nietzsche, ‘with its suggestions of unseen auguries beneath the appearance of things’, which translated into his own unexpected responses to quotidian surroundings and objects. He wrote in 1909 about the ‘host of strange, unknown and solitary things that can be translated into painting ... What is required above all is a pronounced sensitivity’— and both imagination and inclination I would think, to look beyond the surface of accustomed sights, such as the archways and piazzas of Turin where he spent a few days while on his way to Paris in 1911.

The Agonizing Morning, 1912His deserted cityscapes of saturated colour – inspired by the ‘metaphysical aspect’ of Turin, especially its architecture – depict strange streets laid out with illogical perspectives, littered with strange objects, all in the high contrast lighting of the bright Mediterranean sun that produced such long shadows. While he focussed first on these, he gradually moved on to explore cluttered interiors that were sometimes occupied by surreal figures, faceless hybrids of statuary and wooden mannequins.

The Agonizing Morning, 1912His deserted cityscapes of saturated colour – inspired by the ‘metaphysical aspect’ of Turin, especially its architecture – depict strange streets laid out with illogical perspectives, littered with strange objects, all in the high contrast lighting of the bright Mediterranean sun that produced such long shadows. While he focussed first on these, he gradually moved on to explore cluttered interiors that were sometimes occupied by surreal figures, faceless hybrids of statuary and wooden mannequins.

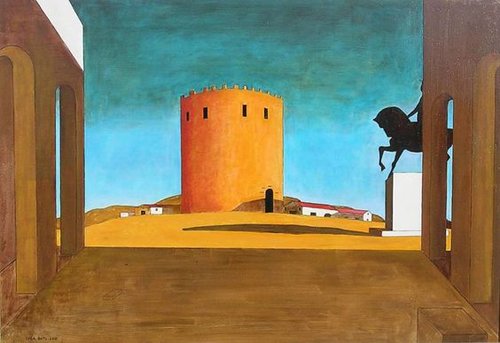

The Red Tower, 1913

The Red Tower, 1913 Fleeing Horse, 1917But it is the cityscapes that I love the most, for their disquieting sense of mystery and emptiness, a kind of visual poetry. I would like to run into those paintings, just like the girl with the hoop in Mystery and Melancholy of a Street, to explore those empty streets and discover what is hiding around the corner.

Fleeing Horse, 1917But it is the cityscapes that I love the most, for their disquieting sense of mystery and emptiness, a kind of visual poetry. I would like to run into those paintings, just like the girl with the hoop in Mystery and Melancholy of a Street, to explore those empty streets and discover what is hiding around the corner.

The Nostalgia of the Infinite, 1913

The Nostalgia of the Infinite, 1913

All images found on Pinterest

Simply Colour

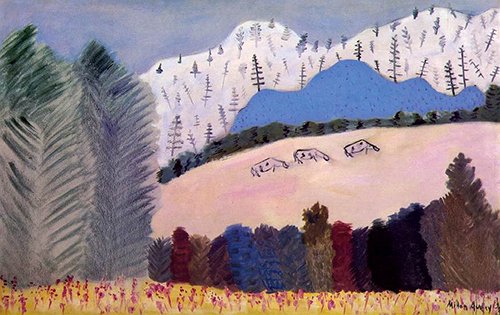

Gaspé – Pink Sky, 1940Can you believe I had never heard of the painter Milton Avery before today? Thanks to Pinterest I discovered his beautiful paintings. The large stretches of almost flat colour of the first one I saw, Gaspé – Pink Sky (1940) immediately put me in mind of Rothko, except that it was representational. What I love about it besides the muted tertiary hues is the simplicity of the stylised shapes that form the landscape, and indeed all his compositions.

Gaspé – Pink Sky, 1940Can you believe I had never heard of the painter Milton Avery before today? Thanks to Pinterest I discovered his beautiful paintings. The large stretches of almost flat colour of the first one I saw, Gaspé – Pink Sky (1940) immediately put me in mind of Rothko, except that it was representational. What I love about it besides the muted tertiary hues is the simplicity of the stylised shapes that form the landscape, and indeed all his compositions.

Seated Lady, 1953

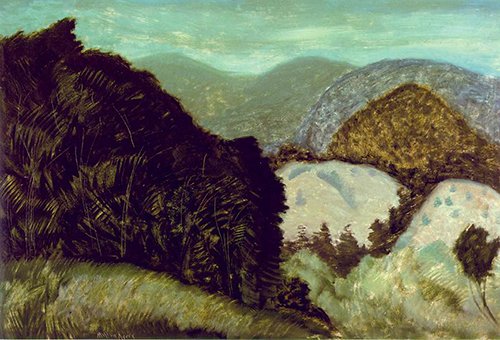

Seated Lady, 1953 Conversation, 1956Avery (1885–1965) is considered a seminal American painter but seemed to have suffered from first being ahead of his times (too abstract early in his career), and when the times caught up and Abstract Expressionism bypassed him, he was dismissed as being too representational.

Conversation, 1956Avery (1885–1965) is considered a seminal American painter but seemed to have suffered from first being ahead of his times (too abstract early in his career), and when the times caught up and Abstract Expressionism bypassed him, he was dismissed as being too representational.

Like Rothko, he was concerned with the relation of colour as opposed to creating the illusion of depth, and was influenced early on by French Fauvism and German Expressionism. He was likened to an American Matisse (another of my favourite artists), and the art critic Hilton Kramer said of him:

“He was, without question, our greatest colorist … Among his European contemporaries, only Matisse—to whose art he owed much, of course—produced a greater achievement in this respect.” [Wikipedia]

Three Cows on a Hillside, 1945

Three Cows on a Hillside, 1945 Fall in Vermont, 1935

Fall in Vermont, 1935 Horse in a Landscape, 1941

Horse in a Landscape, 1941 Vermont Hills, 1936Working in New York City in the 1930s–40s he became a part of the artistic community and in fact friends with Mark Rothko, who paid him a high compliment:

Vermont Hills, 1936Working in New York City in the 1930s–40s he became a part of the artistic community and in fact friends with Mark Rothko, who paid him a high compliment:

“What was Avery’s repertoire? His living room, Central Park, his wife Sally, his daughter March, the beaches and mountains where they summered; cows, fish heads, the flight of birds; his friends and whatever world strayed through his studio: a domestic, unheroic cast. But from these there have been fashioned great canvases, that far from the casual and transitory implications of the subjects, have always a gripping lyricism, and often achieve the permanence and monumentality of Egypt.” [Wikipedia]

Read about him in more detail here.

Yellow Sky, 1958

Yellow Sky, 1958 Interlude, 1960Images from Wikiart and Pinterest.

Interlude, 1960Images from Wikiart and Pinterest.

A Match Made in Wonderland

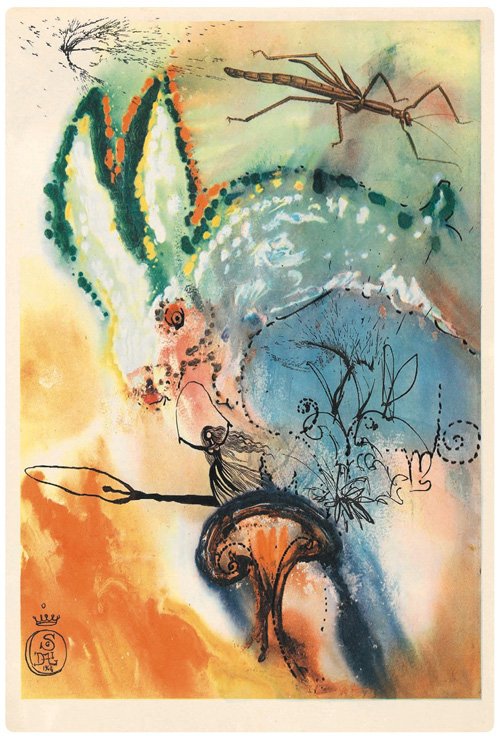

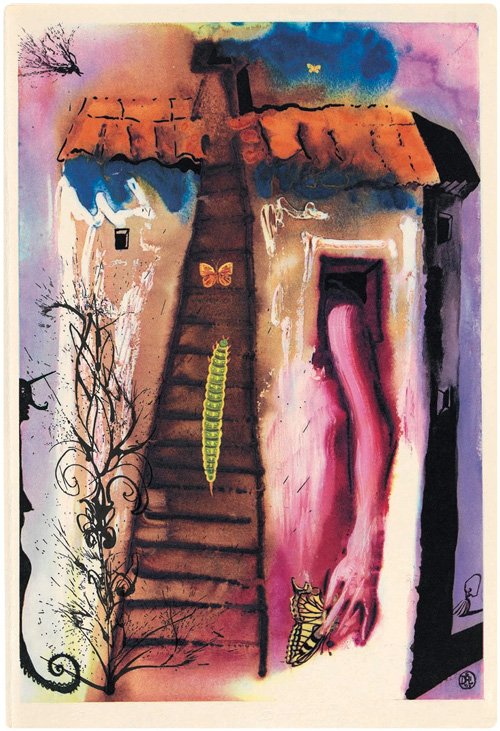

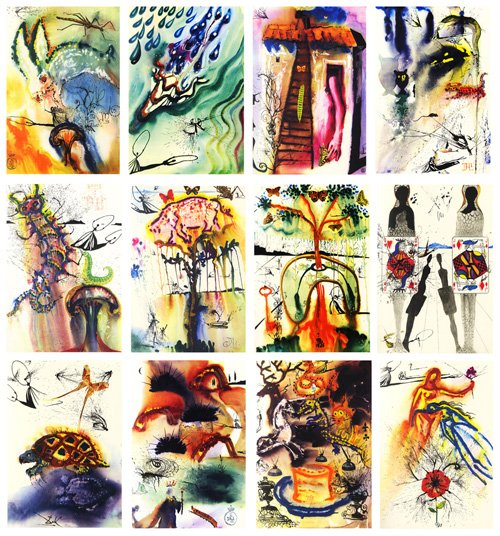

While I am not a big fan of Salvador Dalí’s work, I must admit that pairing him with Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (a childhood favourite of mine) was a stroke of brilliance. An editor at Random House commissioned the artist to illustrate an exclusive edition of the book in the 1960s, with all copies signed by the artist.

While I am not a big fan of Salvador Dalí’s work, I must admit that pairing him with Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (a childhood favourite of mine) was a stroke of brilliance. An editor at Random House commissioned the artist to illustrate an exclusive edition of the book in the 1960s, with all copies signed by the artist.

The book celebrated its 150th anniversary two years ago, and this edition was was published for the public by Princeton University Press. Currently in Melbourne, the Australian Centre of the Moving Image is presenting a world premiere exhibition celebrating the tale as it has appeared on film, so I’m keeping my fingers crossed that this book might be amongst the merchandise on sale.

The book celebrated its 150th anniversary two years ago, and this edition was was published for the public by Princeton University Press. Currently in Melbourne, the Australian Centre of the Moving Image is presenting a world premiere exhibition celebrating the tale as it has appeared on film, so I’m keeping my fingers crossed that this book might be amongst the merchandise on sale.

Here is the phantasmagorical result of Dalí’s reimaginings of the famous tale. Read more here.

Six Cats

January’s catLast December I started shopping for this year’s calendar early – I didn’t want a repeat of the year before when I really struggled on New Year’s Eve to find something that I liked. I don’t recall where I found this ‘Cats in Posters’ calendar by Catch Publishing, but as always my criteria was nice pictures and nice paper.

January’s catLast December I started shopping for this year’s calendar early – I didn’t want a repeat of the year before when I really struggled on New Year’s Eve to find something that I liked. I don’t recall where I found this ‘Cats in Posters’ calendar by Catch Publishing, but as always my criteria was nice pictures and nice paper.

Unfortunately there is no information about the source material, but clearly the paintings range over a few decades and nations. I have been enjoying the first six months of pictures, but I think my favourite so far has to be June’s amusing Dutch black cat holding a spool of Zwicky thread like a harmonica.

February’s cat

February’s cat March’s cat

March’s cat April’s cat

April’s cat May’s cat

May’s cat June’s cat

June’s cat

Bonne Fête

Rue Montorgueil, Paris, Festival of June 30, 1878, painted by Claude Monet in 1878“The Fête de la Fédération on 14 July 1790 was a celebration of the unity of the French nation during the French Revolution. The aim of this celebration, one year after the Storming of the Bastille, was to symbolise peace.

Rue Montorgueil, Paris, Festival of June 30, 1878, painted by Claude Monet in 1878“The Fête de la Fédération on 14 July 1790 was a celebration of the unity of the French nation during the French Revolution. The aim of this celebration, one year after the Storming of the Bastille, was to symbolise peace.

“On 30 June 1878, a feast was officially arranged in Paris to honour the French Republic (the event was commemorated in a painting by Claude Monet).” [Wikipedia]

And here is Monet’s painting, full of joy and light – you can practically feel the sunlight and the wind on your face emanating from exhilarating painting, with all those madly waving flags. And it is easy to imagine how the air must have been alive with excitement and celebration. What an extraordinary impression Monet captured of such a momentous day.

Happy Bastille Day to my French readership!