Simply Colour

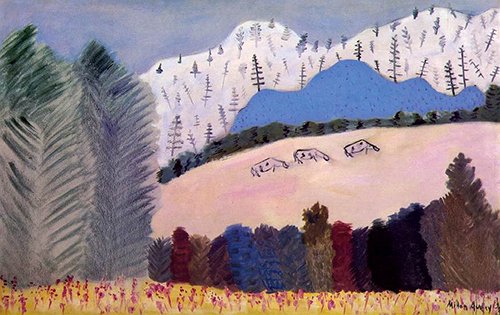

Gaspé – Pink Sky, 1940Can you believe I had never heard of the painter Milton Avery before today? Thanks to Pinterest I discovered his beautiful paintings. The large stretches of almost flat colour of the first one I saw, Gaspé – Pink Sky (1940) immediately put me in mind of Rothko, except that it was representational. What I love about it besides the muted tertiary hues is the simplicity of the stylised shapes that form the landscape, and indeed all his compositions.

Gaspé – Pink Sky, 1940Can you believe I had never heard of the painter Milton Avery before today? Thanks to Pinterest I discovered his beautiful paintings. The large stretches of almost flat colour of the first one I saw, Gaspé – Pink Sky (1940) immediately put me in mind of Rothko, except that it was representational. What I love about it besides the muted tertiary hues is the simplicity of the stylised shapes that form the landscape, and indeed all his compositions.

Seated Lady, 1953

Seated Lady, 1953 Conversation, 1956Avery (1885–1965) is considered a seminal American painter but seemed to have suffered from first being ahead of his times (too abstract early in his career), and when the times caught up and Abstract Expressionism bypassed him, he was dismissed as being too representational.

Conversation, 1956Avery (1885–1965) is considered a seminal American painter but seemed to have suffered from first being ahead of his times (too abstract early in his career), and when the times caught up and Abstract Expressionism bypassed him, he was dismissed as being too representational.

Like Rothko, he was concerned with the relation of colour as opposed to creating the illusion of depth, and was influenced early on by French Fauvism and German Expressionism. He was likened to an American Matisse (another of my favourite artists), and the art critic Hilton Kramer said of him:

“He was, without question, our greatest colorist … Among his European contemporaries, only Matisse—to whose art he owed much, of course—produced a greater achievement in this respect.” [Wikipedia]

Three Cows on a Hillside, 1945

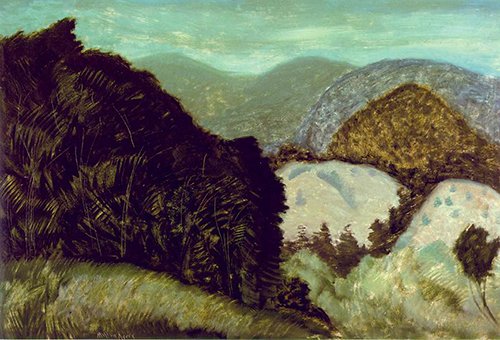

Three Cows on a Hillside, 1945 Fall in Vermont, 1935

Fall in Vermont, 1935 Horse in a Landscape, 1941

Horse in a Landscape, 1941 Vermont Hills, 1936Working in New York City in the 1930s–40s he became a part of the artistic community and in fact friends with Mark Rothko, who paid him a high compliment:

Vermont Hills, 1936Working in New York City in the 1930s–40s he became a part of the artistic community and in fact friends with Mark Rothko, who paid him a high compliment:

“What was Avery’s repertoire? His living room, Central Park, his wife Sally, his daughter March, the beaches and mountains where they summered; cows, fish heads, the flight of birds; his friends and whatever world strayed through his studio: a domestic, unheroic cast. But from these there have been fashioned great canvases, that far from the casual and transitory implications of the subjects, have always a gripping lyricism, and often achieve the permanence and monumentality of Egypt.” [Wikipedia]

Read about him in more detail here.

Yellow Sky, 1958

Yellow Sky, 1958 Interlude, 1960Images from Wikiart and Pinterest.

Interlude, 1960Images from Wikiart and Pinterest.

A Beautiful Soul

Only very recently did I discover the ethereal work of Scottish photographer Lady Clementina Hawarden (1822–1865), via an Instagram page called VictorianDarlings.

Only very recently did I discover the ethereal work of Scottish photographer Lady Clementina Hawarden (1822–1865), via an Instagram page called VictorianDarlings.

For a moment they took my breath away, for there was something achingly poignant and tender about them: the soft natural light that gently bathed these young women and diffused into grand interiors, this glimpse of a woman’s exploration of her subject – her daughters, mostly – in the pioneering days of photography.

Produced by albumen prints from wet-collodian negatives, the most popular method in the mid 19th century, Hawarden’s photographs are like paintings, sumptuous and delicate at the same time.

Produced by albumen prints from wet-collodian negatives, the most popular method in the mid 19th century, Hawarden’s photographs are like paintings, sumptuous and delicate at the same time.

Hawarden called her work ‘studies’, and she worked in natural light, unlike many of her contemporaries, using mirrors to distribute the light pouring into her interiors through huge windows or French doors. In largely empty rooms, she used props, mirrors, draped fabric and curtains, and clothing made up of both contemporary and costume dress to create exquisite portraits, and tableaux (a popular theme of the era) of her daughters.

Windows, an obvious and convenient source of light, become a framing device, and offer a glimpse of the balcony beyond; further off, the city becomes a blurred background.

Most of what is known about Hawarden must be gleaned from her work; some art critics have made suppositions about her themes, for instance, exploring sexuality and adolescence, subjects that bothered the Victorians; but that can only be guesswork, and dubious at that when viewed through a contemporary lens (no pun intended). She left no diaries, nor was there any accompanying archival material when the photographs were generously donated to the V&A Museum by her granddaughter in 1939. They were cut or torn from family albums – there is no explanation as to why, but my guess is stubborn glue! (Sometimes the simplest answer is the right one.)

Most of what is known about Hawarden must be gleaned from her work; some art critics have made suppositions about her themes, for instance, exploring sexuality and adolescence, subjects that bothered the Victorians; but that can only be guesswork, and dubious at that when viewed through a contemporary lens (no pun intended). She left no diaries, nor was there any accompanying archival material when the photographs were generously donated to the V&A Museum by her granddaughter in 1939. They were cut or torn from family albums – there is no explanation as to why, but my guess is stubborn glue! (Sometimes the simplest answer is the right one.)

I think Hawarden found a creative outlet that thrilled her – she produced her entire oeuvre (over 800 photographs) by painstaking method in only approximately seven years – and in an era when this art form was so new, above all she wanted to make beautiful pictures. Is that not enough without casting about for bogeymen? To me, the photographs speak for themselves – and of her beautiful soul.

I think Hawarden found a creative outlet that thrilled her – she produced her entire oeuvre (over 800 photographs) by painstaking method in only approximately seven years – and in an era when this art form was so new, above all she wanted to make beautiful pictures. Is that not enough without casting about for bogeymen? To me, the photographs speak for themselves – and of her beautiful soul.

Read more about Lady Clementina Hawarden and see more of her work at V&A Museum.

Images from V&A Museum, and Pinterest.

Bonne Fête

Rue Montorgueil, Paris, Festival of June 30, 1878, painted by Claude Monet in 1878“The Fête de la Fédération on 14 July 1790 was a celebration of the unity of the French nation during the French Revolution. The aim of this celebration, one year after the Storming of the Bastille, was to symbolise peace.

Rue Montorgueil, Paris, Festival of June 30, 1878, painted by Claude Monet in 1878“The Fête de la Fédération on 14 July 1790 was a celebration of the unity of the French nation during the French Revolution. The aim of this celebration, one year after the Storming of the Bastille, was to symbolise peace.

“On 30 June 1878, a feast was officially arranged in Paris to honour the French Republic (the event was commemorated in a painting by Claude Monet).” [Wikipedia]

And here is Monet’s painting, full of joy and light – you can practically feel the sunlight and the wind on your face emanating from exhilarating painting, with all those madly waving flags. And it is easy to imagine how the air must have been alive with excitement and celebration. What an extraordinary impression Monet captured of such a momentous day.

Happy Bastille Day to my French readership!

Serene Greens

Interior, 1920

Interior, 1920

Pinterest gave me a present today, a whole page full of Henri Matisse artworks that I might like! Immediately this painting of a bedroom interior caught my eye, and made me sigh enviously. It just looks so serene and inviting. In fact, a work colleague saw it on my computer screen at a distance and had the same reaction. “I LOVE it!” she exclaimed very positively.

Here is a series of his paintings in similar tones that are equally evocative and sigh-inducing.

The Terrace, 1906

The Terrace, 1906 The Window, 1916

The Window, 1916 The Artist's Garden at Issy les Moulineaux, 1918

The Artist's Garden at Issy les Moulineaux, 1918 Flowers, 1903

Flowers, 1903

Rebels of Colour

Study for the Portrait of Madame Heim, 1926I was going to write a story on the inspirational Sonia Delaunay, one of my favourite artists and textile designers, but instead I discovered the work of her husband Robert, with which I had been hitherto shockingly unfamiliar. I don’t even recall studying him when I was at art school!

Study for the Portrait of Madame Heim, 1926I was going to write a story on the inspirational Sonia Delaunay, one of my favourite artists and textile designers, but instead I discovered the work of her husband Robert, with which I had been hitherto shockingly unfamiliar. I don’t even recall studying him when I was at art school!

Robert Delaunay (1885–1941) was born in Paris, and after his parents divorced, was brought up by his aunt and uncle, who sent him to study Decorative Arts at Ronsin’s atelier in 1902. At age 19, he left the atelier to focus entirely on painting, and in subsequent years was contributing paintings to the Salon des Indépendents.

Portrait of Henri Carlier, 1906His Neo-Impressionist style employed the use of mosaic-like cubes to form his small but intricate paintings, and he was linked with the Cubists, but in 1911 (by this time married to Sonia) his work became nonfigurative as he explored the ‘optical characteristics of brilliant colour that was so dynamic they functioned as form’. [Wikipedia] He and Sonia, along with others, founded Orphism, an offshoot of Cubism, which focused on pure abstraction and bright colours.

Portrait of Henri Carlier, 1906His Neo-Impressionist style employed the use of mosaic-like cubes to form his small but intricate paintings, and he was linked with the Cubists, but in 1911 (by this time married to Sonia) his work became nonfigurative as he explored the ‘optical characteristics of brilliant colour that was so dynamic they functioned as form’. [Wikipedia] He and Sonia, along with others, founded Orphism, an offshoot of Cubism, which focused on pure abstraction and bright colours.

The First Disk, 1913

The First Disk, 1913 Circular Forms: Sun No 1, 1912–13In 1912, Delaunay said, ‘I made paintings that seemed like prisms compared to the Cubism my fellow artists were producing. I was the heretic of Cubism. I had great arguments with my comrades who banned color from their palette, depriving it of all elemental mobility. I was accused of returning to Impressionism, of making decorative paintings, etc … I felt I had almost reached my goal.’ [Wikipedia]

Circular Forms: Sun No 1, 1912–13In 1912, Delaunay said, ‘I made paintings that seemed like prisms compared to the Cubism my fellow artists were producing. I was the heretic of Cubism. I had great arguments with my comrades who banned color from their palette, depriving it of all elemental mobility. I was accused of returning to Impressionism, of making decorative paintings, etc … I felt I had almost reached my goal.’ [Wikipedia]

‘I made paintings that seemed like prisms compared to the Cubism my fellow artists were producing.’

Delaunay went on to be invited by Wassily Kandinsky to join Die Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider), a Munich-based group of abstract artists, and to enjoy success in Switzerland and Russia as well. Orphism as a movement however was short-lived, losing its novelty as a new artistic style, coming to an end before the onset of the First World War. Despite this, both the Delaunays essentially adhered to its theories in their subsequent work.

Astra (also known as Study for 'The Football Players of Cardiff'), 1912–13 While living in Madrid during WWI, Delaunay was stage designer for Sergei Diaghilev on the ballet Cleopatra; Sonia did costume design. While he continued to paint after the war, he also was involved in the design of railway and air travel pavilions for the 1937 World Fair in Paris. He died at age 56 in 1941 from cancer.

Astra (also known as Study for 'The Football Players of Cardiff'), 1912–13 While living in Madrid during WWI, Delaunay was stage designer for Sergei Diaghilev on the ballet Cleopatra; Sonia did costume design. While he continued to paint after the war, he also was involved in the design of railway and air travel pavilions for the 1937 World Fair in Paris. He died at age 56 in 1941 from cancer.

I love the idea that the Delaunays, and others of their group, were boldly running complete counter to their contemporaries, such as Picasso and Braque, and pursuing their own vision in celebration of colour for its own sake. And why not? The world would be a dreary place indeed if it was seen only in black and white.